Session 01 LEVELS OF PMF

Product-Market Fit Isn’t a Black Box — A New Framework to Help B2B Founders Find It, Faster

Most people describe finding product-market fit as an art, not a science. But when it comes to sales-led B2B startups, we’ve reverse engineered a method to increase the odds of unlocking it. We’ve worked with some of the world’s most iconic enterprise founders and distilled what they did in their first six months into a series of tactical sessions for taking a straighter path to PMF. Today, we’re open sourcing the first session, which shares how we’ve broken PMF down to an incredibly granular level in order to help more builders get there faster.

Even though finding product-market fit is the single most important objective any company must achieve, it’s still a black box for founders — seemingly requiring some mysterious combination of luck, market timing, and sheer grit.

While much has been written on the topic, no one has broken down the inputs, leading indicators and tactical steps that could increase the odds of finding PMF. In our view, one of the key reasons this topic hasn’t been successfully “framework-ified” is that most folks still talk about the concept in generalities.

Fish are jumping into the boat. Leads are falling on the floor. You’re chasing — not pushing — a boulder. The product is being pulled out of your hands. You’ll know it when you see it. You can feel when it’s not happening. These descriptions lack the specificity that we see in other areas of company building.

Another issue? Most resources target a wide range of builders — which results in watered-down advice that’s more hand-wavy than tactical. Founders are left with approaches that are neither replicable nor practical, ranging from unhelpful “We kind of just started going viral” founding stories to one-size-fits-all frameworks that don’t address the nuances of their specific business.

While the hunt for PMF can be more of a dice game with poor odds for, say, consumer apps, our experience has taught us that for sales-led B2B companies, you can reduce the role of luck.

Here’s how we’ve developed that conviction: As a firm of former founders and startup builders, we’re coming up on our 20th year of investing in pre-product-market fit startups. Along with Square, Notion, Looker, and Verkada, we’ve backed hundreds of companies when they were just a couple of founders and an idea.

Drawing on our own data and observations from more than 500 investments, we’ve spent the last several years breaking down the decade-long project of building a category-defining B2B company into more concrete steps — in hopes that we could create this resource that we feel is missing from the ecosystem.

To put it even more plainly: Despite all the talk about product-market fit, it didn’t seem like anyone was meaningfully putting the pieces together to help B2B founders increase their odds of finding it. We wanted to change that.

In addition to distilling lessons from decades of our own experience, we’ve layered on hundreds of hours of research and interviewed dozens of founders who’ve gotten further on this journey than most, from both within and outside of our community. (If you’re a regular reader of The Review, you may have noticed that we’ve started publishing some of these stories in our series Paths to PMF — focusing on the down-in-the-weeds details of how companies from Vanta to Vercel took off.)

As the culmination of that work, today we’re proud to unveil Product-Market Fit Method, an intensive 14-week experience designed to help exceptional pre-seed founders build epic B2B SaaS companies. From proven tactics to detailed benchmarks that help founders gauge progress, we’ve mined the secrets that are buried in the best B2B builders’ experiences to create a new methodology that helps startups take a straighter path to PMF.

The program (which kicks off on May 29 and can be applied for here) consists of eight tactical sessions. We’ll cover everything from validating your product insight and market, to approaching positioning, design partners, and product iteration, to learning the ropes of what we call “dollar-driven discovery” and founder-led sales.

While this is currently a highly-curated program with a limited number of spots, our tradition here at First Round has been to open-source everything we can to share what we’ve learned with the broader startup ecosystem — whether it’s a decade of advice on The Review or years spent building communities like Angel Track. In keeping with that spirit, we’ve decided to publish the content of the first session in full, as a preview.

No commitment to applying. No email paywall (although of course, we’d highly recommend subscribing to The Review newsletter). No charge. And no equity required for the program either — our aim is to increase the odds that more founders find product-market fit, whether they’re backed by First Round or not.

The deck may seem stacked, but we're on a mission to rebalance the odds in the early founder's favor. We’re firm believers that you don’t have to go at it alone — and you don’t have to make it all up as you go either.

We’ve taken a systematic approach to defining what product-market fit is and identifying truly tactical steps for how to go about finding it. But to be very clear, the first session that we’re open-sourcing here is all about exploring the former, breaking down the elements of PMF so it’s easier to unlock. The rest of the sessions in PMF Method tackle the latter in much greater detail — with expert-led workshops, practical exercises and templates, actual customer introductions, and unique access to our network of established founders and angel investors.

With that, let’s dive in.

Levels of PMF

INTRODUCING EXTREME PRODUCT-MARKET FIT

Let’s start with the obvious question: What is product-market fit? Here’s our specific definition of what founders are aiming for — and why it’s a bit different from what you may have seen before:

Extreme product-market fit is a state of widespread demand for a product that satisfies a critical need and — crucially — can be delivered repeatably and efficiently to each customer.

As we’ve noted, the way most people have talked about product-market fit feels insufficient. More specifically, there are certain nuances that we feel haven't yet been adequately addressed:

Product-market fit progresses in levels. It’s not a binary state where you have it and you’re golden, or you don’t and you’re not on the path. But it’s also not a vague spectrum or fuzzy sliding scale, where you can’t be sure where you’re at.

There are a few dimensions of PMF that are in tension with each other, requiring deliberate tradeoffs at each level. There isn’t just one element to emphasize above all else. And importantly, there are different times in a company’s lifespan where founders need to intentionally prioritize one over another.

There isn’t nearly enough emphasis on repeatability. As you move your way up through the different levels of product-market fit, what you’re really unlocking is repeatability — across demand generation, product development, customer satisfaction and unit economics. A startup hasn’t reached the upper levels of product-market fit until it has developed a fine-grained understanding of who the right customer is, how to land them, and how to deliver a product that (in most cases) isn’t bespoke for each customer yet consistently solves a significant need. In a nutshell, you don’t have to work as hard to find what we’re calling your “marginal customer” (more on that in the section below).

Repeatability is the holy grail on the hunt for product-market fit. Without any patterns, it’s nearly impossible to generate early momentum and plot a course forward.

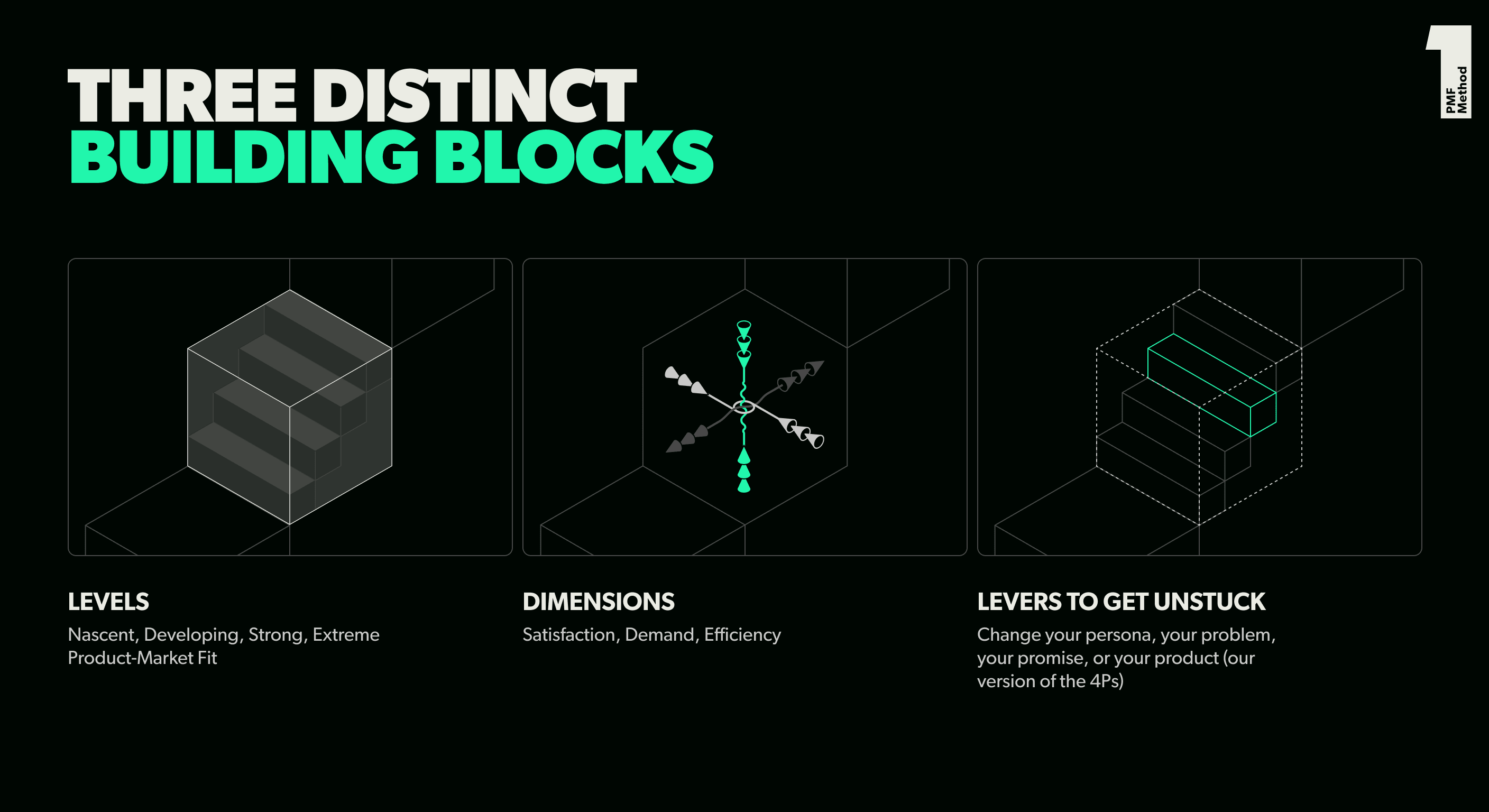

That’s why when we picture product-market fit, we see three distinct building blocks:

Four Levels: Nascent, Developing, Strong, Extreme Product-Market Fit

Three Dimensions: Satisfaction, Demand, Efficiency

Levers: Change your persona, your problem, your promise, or your product (our version of the 4Ps) to make the work of finding, winning, serving and retaining your marginal customer easier.

To be clear, pieces of this approach may exist here or there in different frameworks — after all, all great ideas are built on what's come before. But our hope is that we're bringing things together and diving deeper into the details in a way that's unique and valuable — plus we’ll take the added step of sharing how a company, Looker, made its way to product-market fit, sharing its actual data across the years. Let’s dig into each one.

The 4 Levels of Product-Market Fit

We’ve identified four concrete levels of PMF, with what we’re calling extreme product-market fit as the ultimate goal — what’s required to build a generational company.

Rather than a blanket “you’ll know it when you have it,” we’ve found that for enterprise companies there's a clear progression that companies go through that is fairly predictable. Many founders have walked this path, and based on what we’ve seen from the hundreds of early-stage startups we’ve backed, this journey to extreme product-market fit usually takes anywhere from two to six years.

Our contention is that product market fit is not binary — and it's not something that you get to overnight, despite what all of those “we just went viral” founding stories may have you believe.

Once in a while, a company shoots up the ladder quickly, but that tends to be the exception. Some companies move up the progression over a longer period of time, while others skip ahead at different moments, leapfrogging from nascent to strong, for example. In our experience, there are a couple of specific timing patterns here that companies fall into, whether it’s making their way through Levels 1-3 quickly but stalling out and never quite hitting Level 4, or reaching Level 1 in record time but then getting trapped at Level 2.

We’ll also note that the journey to PMF is a two-way ladder, meaning levels aren’t permanently unlocked — it is possible to regress. To use another metaphor, think of it more as a dynamic equilibrium. Just like in chemistry, your actions, your competitors’ actions, customer expectations, technology shifts and other factors are all at a tentative equilibrium state. If one of those elements changes — maybe your competitor makes a huge leap forward — and you don’t adjust, you may not be at the same level of PMF anymore. (For another take on this topic, we recommend three-time founder Bob Moore’s framework here.)

We’ll get deep into the details of what progressing through each level feels like further down, but staying at our current altitude, there’s one high-level question you can ask here if you’re unsure where your company stacks up: How hard is it to find and serve your next “marginal” customer? As you move up, it becomes easier and easier, and increasingly more repeatable.

At Levels 3 and 4, for example, demand swells. Contrast that with Levels 1 and 2, where the search for the marginal customer feels more like a battle on several fronts — finding the right person, convincing them that your solution is what they need, converting them, and turning them into satisfied customers.

The 3 Dimensions of Product-Market Fit

We like to break that definition down even further into what we call the three dimensions of product-market fit:

Satisfaction: How happy are customers with the product? Are you able to effectively retain customers? How much do people need the product? It may seem like splitting hairs, but we’ll note that we’ve intentionally used “need” and not “love” here — there are many companies that have extreme PMF without customer love. (Salesforce is an example of a product that’s perhaps not beloved, but certainly satisfies a critical customer need.)

Demand: Do you have the proverbial “lines out the door”? How quickly and how much can you sell your product for?

Efficiency: Can the product grow repeatably and scale effectively? In our view, this is the critical piece that many definitions of PMF gloss over — even though it’s one of the most important things that a company must achieve. Here’s how we like to break it down: efficiency in finding the customer (CAC), selling and closing the customer (sales conversion, magic number, CAC payback), in activating and supporting the customer (length of integration cycle, NRR), in producing the product (COGS, gross margin), and across the company as a whole (burn multiple).

Some may bristle at that last one. Most other definitions of product-market fit overtly focus on satisfaction and demand, implying that efficiency takes care of itself in the long run. But our belief is that while your business won’t be efficient from day one — and may in fact be intentionally inefficient while you work to figure things out at Level 1 — there is tremendous value in building with an eye towards efficiency throughout your entire journey as a founder.

As a thought exercise, say you open up a stand on the side of the road where anyone who lines up and gives you $1 gets $100 in return. By classic definitions, product-market fit would be off the charts. You'd have lines out the door. Customers would be very satisfied. But it would be a mirage. And a particularly dangerous one at that, given the risk that you’ll lull yourself into the false belief that you’ve unlocked PMF.

When you’re starting a marathon, it’s helpful to know what the final mile needs to look like — even if you don’t alter your approach to mile 1. If you keep efficiency in the back of your mind even at the earlier stages, you’ll be able to stay intentional in the tradeoffs you’re making as you build.

One final note here: These dimensions are actually highly intertwined — and require distinct tradeoffs in different scenarios. For example, you can take on several initiatives to increase efficiency — spending less time doing unscalable things, automating and operationalizing more aspects of your business — but in many instances, that harms the customer experience, reducing satisfaction. (Of course, there are times where there’s more harmony than discord — for example, shipping a critical product feature might improve all three at once.)

The First Round 4Ps: Levers to Get Unstuck on Your Path to Product-Market Fit

As for how you can get unstuck and catapult your company to the next level, you can experiment with pulling these four levers at various points along your journey (our spin on the classic 4Ps framework):

The persona: Who would benefit most from your insight? Do you have a person in a specific type of role or function who faces a set of challenges in mind? In this context, the persona can be the buyer (CTO or CRO), the company type (e.g. Fortune 10,000 financial services) or both. As you look to make adjustments here, consider whether it’s too narrow, too broad — or needs to be abandoned altogether. Example from Plaid: Consumers didn’t need another budgeting app, but fintech apps needed the integrations the team had built on the back-end.

The problem: Is this an urgent and important problem that your target persona has? It’s the classic painkiller versus vitamin question. You’re looking to solve a problem that is urgent and, if solved, will provide huge relief to your potential customers. If not, you may need to explore adjacent problems for your persona, or rethink your persona and problem entirely. Example from Lattice: Stayed focused on people leaders, but went from building a solution for OKRs to solving performance management.

The promise: Are those customers interested in what you’ll do to address that need — your unique value proposition? It’s easy to confuse this for your actual product, but the promise is how you communicate the benefit your product will deliver. In our experience, this is the lever that is most overlooked. Example from Ironclad: Repositioned from an AI legal assistant (that promised to automate lawyers’ tasks) to a Contract Lifecycle Management platform (that promised to help enterprise companies create and manage legal contracts end-to-end) in order to play in an existing category.

The product: Will the product that you’re building actually deliver on this promise? Are customers interested in this particular solution to their problem? Would they pay for it? Example from Alma: Pivoted during the pandemic from a community-based physical office concept for therapists, to giving providers a suite of digital tools to build thriving private practices.

For example, a startup might be stuck at developing PMF, but later find that pivoting to a new buyer is the move that unlocks the next level. Or another company may have stumbled onto nascent PMF with resonant positioning, but then can’t ship the correct product that delivers on its promise.

These levers, of course, fall more into the camp of how to go about finding PMF, which is not the focus of this essay. (But in PMF Method, we have a full session dedicated to each of these levers, filled with tactics, real-world examples, and hands-on exercises to better guide you.)

What Extreme Product-Market Fit Looks Like in the Real World:

To bring this new concept of extreme product-market fit to life, let’s walk through an example from Looker when it reached this Level 4 milestone as a Series C company with a team of 235 at the end of 2016 — after five years of hard work progressing through Levels 1-3. (You’ll notice how the curve starts to inflect right around this timeframe in the chart below, taken from the company’s April 2018 board deck.)

Here’s how Looker checked each box on our list of the three dimensions at this time:

Demand: Went from 450 to nearly 800 customers in a year, growing revenue from $11.5M to $27M and increasing ACV to $57.7K.

Satisfaction: Extremely happy customers, with 141% NRR, an 18 month-streak of net negative churn and renewals higher than plan.

Efficient: The company had built an efficient model, with 77.6% gross margin.

Looker’s path is a great example of each dimension coming together to contribute to extreme product-market fit (and we’ll be sharing more of it in the pages below). But just as there are success stories like these, in our experience, the absence of one or more of these dimensions is also the biggest reason that startups fail.

We believe that if you think about PMF in these terms, you'll be more likely to end up at strong or extreme levels of PMF than all the companies that didn't make it — in part because you and your co-founders will have a shared framework to more precisely diagnose where you might be falling short.

To help your startup achieve that feat, we’ll dive into each of these levels and unpack them with more detail. In the sections that follow, we’ll walk you through what it feels like to be at each one, the most important thing to focus on, and thought starters from fellow founders on what you might try to level up.

In addition to benchmarks based on data we’ve gathered and insights from established B2B founders who are where you want to be, we’ve also drawn from the hundreds of companies we’ve worked with to create composite case studies of fictitious startups that bring each level to life. We’ll also return to our example of how Looker actually progressed through every level and eventually reached extreme product-market fit.

Level 1

Nascent

At this stage, a founder’s primary job is to find a problem worth solving for three to five customers. And by problem we mean an issue that is urgent and important for them, where solving it would be immensely valuable for their business. With that in sight, it’s time to build a product that solves the problem and delivers high satisfaction for those customers. You may need to iterate across our 4Ps (persona, problem, promise, product) a few times to land on the right combination.

And while it’s not the primary focus of Level 1, you should also be thinking about demand here, exploring whether you’ll be able to find enough customers with that problem who will need your product. While efficiency isn't something to spend much time on yet, we’d recommend trying to start constructing a credible argument in your head about how the business could eventually scale efficiently.

In our experience, we’ve found that a fairly high percentage of startups get stuck at Level 1 — and stay stuck for six, 12, or even 18 months. That's when we’ve seen founders get bogged down in “the grind.”

That’s because the hallmark of this level is that it lacks repeatability — that’s to be expected at Level 1. Finding the marginal customer is the opposite of easy. At this point, you’re not entirely clear on what a customer needs to look like in order to be the right fit for what you’re building. And even when you land on a rough hypothesis, acquisition is usually unscalable. Then when you do get in front of a prospect, your messages don’t always land — some customers immediately “get it,” while for others it doesn’t resonate.

Each customer’s needs (and thus the solutions that you build) are slightly different. Some come in asking for a slew of additional features and functionality to meet their requirements, while others see an immediate impact even with an early version of the product.

What is Feels Like

As we talked to sales-led B2B founders about how they navigated this first phase, unsurprisingly, several different paths emerged. Some grappled with finding the right product, others struggled to identify the target user, still others doubted the size of the market or even abandoned their original idea entirely.

The common thread was wasted cycles before they stumbled upon those first few sparks of traction — which were more in the vein of “aha moments” or “this might just work” inklings, rather than hard metrics and the beginning of a hockey stick growth curve.

Here are three specific examples from Ironclad, Verkada and Plaid on what that early traction felt like (after a winding path to getting there):

Ironclad: Unlocking a more specific product by visiting customers IRL

Ironclad is now a well-known digital contracting platform (last valued at $3.2B), but unpacking their journey to nascent product-market fit highlights just how much manual, non-scalable work you’ll find at this level.

After serving as outside counsel for startups, co-founder Jason Boehmig started tinkering with automating parts of his own practice with coding that he had taught himself along the way. After realizing that there was a gap both in new solutions for lawyers and a team that understood how they actually used software products, he decided to leave his law firm life behind.

“It’s wild to think back to this now that we're in the AI assistant boom because the first version of Ironclad was an automated assistant for legal paperwork — but it was really me on the backend of an email address,” Boehmig says.

“We started by doing everything from corporate filings to NDAs and everything in between. So if you were doing an NDA, you would CC admin@ironclad.ai and be like, ‘Hey, I'm doing an NDA with Joe Smith. Can you help us get it done?’ And I would send a series of responses as the Ironclad AI such as, ‘Hey, I need the following information,’ or ‘Here's the template. I filled it in.’ I later met my co-founder, Cai, who was an amazing engineer, and he’d watch me work as the assistant and then would automate what could be automated away.”

But it was spending time in person with their initial customers that helped narrow their product’s focus. “I remember that we flew out the whole company — which was four or five people at the time —to Boulder to see a customer who had a bunch of product feedback for us. We all just sat around and watched them use the product,” Boehmig says.

“They had two monitors, one showing their email and on the other was Ironclad. They were just doing their day-to-day routine, working on a legal team. And by observing them and seeing how important these routine, repeatable transactions were to their profession, we realized we had to go all in on these corporate legal teams — particularly legal operations, which was a role that was just getting defined back in 2015.”

"At Ironclad, the early ‘aha moments’ came from watching our customers use the product. It enabled us to pick a niche audience that we could go after — legal operations — and the specific task they were doing — routine transactions."

Verkada: Going unreasonably deep and moving fast to wow customers

Verkada has six different physical security product lines today, but the founders started back in 2016 with video security. Inspired by IoT devices in the consumer space, they realized the enterprise equivalent of applying software to video security was missing. When co-founder Filip Kaliszan thinks back to the nascent stage of their journey to PMF, the team’s speed and willingness to get in the field stand out.

“The very first version looked very funny. It was a Raspberry Pi based camera. We just hacked it together from different parts — the supply chain was Amazon.com, We built maybe 100 of these little cameras and we gave them to friends and businesses we knew,” says Kaliszan. “The whole idea was to just learn what it takes to build the software and build out the solution. The prototype was just about learning if the technology would work and convincing ourselves that there was a there there.”

What struck us about Verkada’s approach here was how hands on it was — and how quickly they moved to extract those insights. “For the first few customers, we just did whatever it took to get the customer deployed as fast as possible and then stayed close to that customer to learn what was working for them and what wasn’t. That approach has been extremely informative in shaping everything we build in our products,” he says.

Take this example: “We were very aggressive with sending trial units. The moment we had a positive signal from the customer, we would get them a camera. We made sure that the process was seamless, fast, and easy from the very beginning. If you talked to us today, 24 hours later you’d have a nice box of kit to try it out,” Kaliszan says.

“We were also going on site and doing a lot of installs for customers. This is before we had a partner ecosystem, before we had installers who wanted to work with us. I remember flying to L.A. to install cameras at the Beverly Hills Equinox, one of our early customers. The gym closed at midnight, and we had until 5:00 AM to get the cameras installed. So I'm buying some drills, getting up on a ladder and pulling cables myself. We were making sure whatever needed to get done got done so that the product worked.”

That commitment paid off. “We spent two years building, so 2018 was our first year of sales. In the first couple of months of that year, we got enough pull and demand on the camera front where it was that validation ‘aha’ moment,” Kaliszan says. “We sort of always thought the idea was cool, but that was that moment that really crystallized that what we had built was beginning to work for the customers.”

"When you have any signs of early demand pull, you have to follow it and work as hard as it takes to just make it happen. "

Plaid: Pivoting and building conviction in an unproven market

But even with early customer traction, it can still feel like a slog. Plaid is now known as the pioneer of the “invisible plumbing” fintech infrastructure that powers everything from paying your friends back on Venmo, to making an investment on Robinhood, to buying Bitcoin on Coinbase. But the product actually started out as a consumer budgeting app.

“The response of consumers was such that we pretty quickly realized we weren't going to be any good at building budgeting apps. We tried for a while. We built six different versions of budgeting management, analyzing your spend types of applications and they didn't really ever get any traction,” says co-founder Zach Perret.

“One day, a friend who was one of the early engineers at Venmo came to us and said, ‘Hey, your consumer products are not so good, but I'd like to license the backend that you've built, the way that you've integrated with the banks in order to get the data into your app.’ It took awhile, but eventually we decided to make this pivot and shift over to building the platform,” he says.

“We then had five or seven people who said that they would probably use the product if we built it. We even had one who said they would pay us if we built it. And so it was pretty easy to find nascent product-market fit in that very early stage once we landed on the right idea,” says Perret.

“The bigger challenge for Plaid was that the market didn't really exist. So while we had these five or seven companies that wanted us to build something, the real challenge was market development. That was the reason that almost every VC passed on investing in Plaid in the early stages. They said, ‘You've built an interesting product, it could be useful for some customers, but the market's not very big.’”

"When I think back to the earliest stage of Plaid’s product-market fit journey, the challenge wasn't finding a product that people would buy. It was creating a market around the product that we believed would be very important for the future, but was yet to be proven."

“Convincing ourselves and everyone else that there was a real market here — that financial services space would eventually have startups in it — that was the hardest thing we had to do in the earliest phase,” says Perret.

What it Looks Like: A Case Study on Nascent Demand, Satisfaction, Efficiency in Action

To return to the very beginning of our example from Looker’s actual trajectory, the data platform startup spent roughly from August 2011 to March 2013 in the nascent stage. “We waited almost a year to raise money, until we knew it was a venture business — not every startup is, and you don’t want to get locked in. We were cranking along with customers and revenue. And it wasn’t all nailed down, but we had figured out enough of how go-to-market might work to know that it was workable,” says Looker co-founder Lloyd Tabb.

Here’s how the business looked at the nascent stage: With that early glimmer of traction, Looker raised a $2 million seed round from First Round and PivotNorth in August 2012. By the end of Q1 of 2013, the 9-person team was at $357K in ARR with 15 customers. (Incidentally, five of Looker’s first six customers were First Round companies.) Outside of warm intros, one tactic the team found effective early on was customer events. “We started doing ‘Look&Tell’ customer events super early on compared to other startups. I remember sweating and dragging cases of beer down Market Street to get to an event we were hosting — I think we probably had about eight attendees, but we kept at it and they paid off eventually,” says Tabb’s co-founder Ben Porterfield.

But to show an even more detailed snapshot of what “good” looks like at this level, we present a case study on our first fictitious startup: Ledgerly, a platform that uses LLMs to help accounting teams — complete with very detailed qualitative descriptions and metrics.

The Ledgerly team is pretty new, with just five full-time employees. They raised a $1.2 million pre-seed round earlier this year and they don't even know what their burn multiple is — but that’s appropriate, given how early they are.

Let’s walk through each of the dimensions of product-market fit:

Demand: They only have four customers, all of which they acquired through warm intros from their personal networks or from investors. They don't have an outbound sales machine yet. Three of those customers are paying $15K each, putting them at $45K ARR. (The fourth one is a design partner and isn’t paying yet.) But what you don’t see in these stats is that they actually had to connect with 46 different companies to land these four customers. That’s fairly typical. In the early stages, you're going to talk to a ton of different prospects as you try to figure out the following: who are the customers that are right for you, and who are the customers with a problem that you can solve with a single product. The Ledgerly team doesn’t have any renewals yet since they're so early that none of their customers have hit the one-year mark. They did have one design partner churn due to lack of fit, but they don't consider that regretted churn.

Satisfaction: All of their customers are starting to use the product regularly, at least once a week. Two of them have onboarded multiple users internally. Ledgerly is getting good feedback from the three customers they’ve asked, so they’re starting to see signs of satisfaction, but it's early and anecdotal at this point.

Efficiency: This is the area the team has paid the least attention to, which is appropriate given their stage. Customer onboarding feels too lengthy (currently at eight weeks) and it takes them a lot of time to find qualified leads for new customers (at least five meetings to just find one prospective — not even signed — customer). What’s more is that customers are making a lot of special requests, which is a common feature of the nascent stage. Four customers making four different sets of requests is pulling the team in different directions, but that’s not unusual, given that the team is still zeroing in on the shape of the product and their ideal customer.

Benchmarks:

While the above hopefully gives you a sense of what nascent product-market fit feels like, we’ve also collected these benchmarks that indicate your company is at Level 1 so you can more closely compare your progress.

You’ll notice that repeatability is nowhere in sight — and that some of these metrics that we would take very seriously for later-stage companies don't even apply yet.

Your team is less than 10 people.

You’re at the pre-seed or seed-stage.

Demand source is mostly friends and network, some cold outreach.

Sales conversions: 1 out of every 10-20 warm intros converts to a customer.

3-5 customers.

$0-$500K ARR.

No renewals yet (too early). No regretted churn (some non-regretted).

You don’t even know what your gross margin and burn multiple are (N/A for each).

What Matters Most:

But in addition to knowing how they stack up, founders also need to focus on what matters most in terms of getting to the next level of product-market fit.

To reach Level 2, founders need to focus on satisfaction most. In the case of our fictitious startup, Ledgerly, in order to move the needle on satisfaction, their goal is to increase daily use and number of users at each company and start sending NPS surveys as a regular part of customer interactions. But don’t focus solely on these satisfaction metrics here — staying outcome-oriented is key. This simple rule of thumb is a great reminder: Are you moving the business outcome you promised to move for your customer, and by how much?

With satisfaction front and center, demand is second at this stage. While you don't need heaps of customers, you do need an inkling that if you make this small set of customers happy, eventually there will be that proverbial line out the door. For Ledgerly, this means setting a target of landing two or three more customers in the next few months.

Efficiency comes in last at this stage. We’d recommend that you don't spend a ton of time thinking about it at Level 1. For Ledgerly, its planned optimizations are in service of improving satisfaction and demand. Their goal is to trim customer onboarding down to four weeks and create a faster, more repeatable sales process to improve conversion.

To reach developing product-market fit, you have to build something that at least a handful of customers really, really need. It solves a problem for them. They can't live without it. And that requires earning a very high level of satisfaction first.

Sticking close to your customers early on is key to cultivating that satisfaction. But there’s an important distinction here. “If you're not giving them value, they don't want to be near you,” says Looker’s Lloyd Tabb. “How many surveys do you get as a customer yourself? I just went and had my car repaired and I got a survey, which isn’t going to give me any value. You need to bring them something of value — otherwise you’re just annoying them,” he says.

“For Looker, the search for product-market fit was about figuring out how to deliver the value. For our first four customers, I had different ways of delivering what I was building, from pure consulting to a standalone product. But the problem with just giving someone the software was that they didn't get as much value out of it. I realized I needed to be teaching how to do data as well as delivering a product,” says Tabb.

“What worked best was part product, part service. We used the demo as a chance to build a proof of concept, so we didn’t have a dummy sales pitch version — we always asked the prospect for an actual dataset to play with. Then it was a very quick forward-deploy. We would come in and do a free trial where we would set up the software and teach them how to use it. And then we would watch for engagement,” he says. “Only when there was engagement would we close the deal. We had almost no early churn because we only sold customers who got the value out of it.”

As we’ve noted, inefficiency is expected at Level 1. “The downside was that some of the trials ran a really long time. If we didn’t see that momentum, I’d go back in and be more hands-on to make sure they understood how we could answer all of their data questions,” he says.

"I had no qualms about sinking a disproportionate amount of resources here. In SaaS, focusing on making your customer successful is a retention strategy, not a cost center. Complicated products require education. If you're selling a complicated product, you are in the education business — so the support you provide is everything."

Yellow Flags to Watch Out for:

It’s hard to tell in the moment if you’re mistaking a more tepid response for early traction, or if an extra dose of founder grit will unlock the breakthrough your business needs. Knowing when to keep forging ahead versus when to pull back and pivot is one of the trickiest parts of Level 1.

Persona founder Rick Song had a thoughtful take here on why startups tend to get bogged down at Level 1. “The biggest challenge for a lot of early-stage startups is that they lie to themselves about customer satisfaction. It’s a common trap at this stage to have customers who like but don't love or need your product. I use the relationship analogy a lot internally at Persona: knowing when someone likes but doesn’t love something is very, very difficult but if you’ve ever been in the friend zone, you know that answer,” he says.

To figure out if he was being “friend-zoned” in the early years of Persona, Song sought to build trusted relationships with a handful of his early customers. He talked to them all the time, texted them, grabbed coffee with them, and made sure he was very candid and self-deprecating to get that real feedback. Song would ask questions like the ones below over and over until he got strong enough answers that convinced him they were on the right track:

If a competitor came along and charged you 50% less than what I'm charging you, would you switch?

If we increase the price, is that something that you're going to have a lot of pushback around?

Is Persona a game changer for your company? If Persona went away, how big a deal would that be for you?

You can’t be in the friend zone forever — eventually you have to ask the hard question to find out if they desperately need what you’re building.

If you’re still unsure, here are the yellow flags we recommend watching out for:

Customers respond that if your product disappeared tomorrow, they wouldn’t be disappointed.

Usage is low and not growing over a period of six months.

You have a handful of happy customers, but the most important feature is actually different for each of them — in other words, you're customizing the product too much to make each customer happy. (That puts you in consulting business territory.)

It feels incredibly hard to find new customers.

The sales cycles take too long, and if your champion quits the company, then the deal just falls apart.

Design partners are hesitant about converting to paid or customers just don't seem willing to pay the ACV you’re after.

With the original idea for Lattice, Jack Altman felt this firsthand. “The first thing we built was an OKR software tool. We had seen at our last company that quarterly OKR planning was a painful process for companies. We validated that there was a real problem by talking to a bunch of other companies about how hard it is. The execs get mad at each other. The employees are like, why are we doing this? Nobody adheres. But while it was in fact a real problem, we never built software that truly solved that problem,” says Altman.

“There were two things that made that clear. One, it was really hard to get people to actually pull out their credit cards and pay us. And so a lot of CEOs and people leaders were saying, ‘We'd really like this. We want to manage our OKRs better. We're doing this in spreadsheets currently, it's not great. Can we try it? Can we test it for a quarter? Can we do a monthly thing? Can you give me a login so I can poke around?’ But when we tried to get them to pay, it was very challenging,” says Altman.

“The second issue was that once we did get people into the product — even entire teams where the whole company would do an OKR planning cycle in Lattice — the next quarter didn't come easily. They were like, ‘Ugh, we’ve got to do this.’ And then by the third quarter they were like, ‘This is not happening naturally.’ For the employees, the retention was just not there. So both sides were not strong enough,” he says.

His advice on how to get unstuck rang true for us: “If you’re stuck, your only way out of the nascent stage is big changes, not small changes. A lot of people hang out in nascent and make small changes for years, and that's just a literal waste of everybody's time and resources. Moving up levels of product-market fit or getting unstuck requires more than just incremental steps or giving it more time,” he says.

“You need to remind people of that reality so they don't stay in these loops for too long and instead say, ‘Alright, we're going to just move on and wholesale try a new thing.’ After nine or 10 months of working on OKRs, we got to a place where there wasn’t any line we could draw between what was happening and a business that was going to make any sense for the next round of funding by the time we ran out of money. So we ended up needing to pivot a couple of times before we landed on the thing that really worked, which was performance management.”

"More often than not, if you're working on something that is not getting great traction, you’re probably not a 10% adjustment away — you’re probably a 200% adjustment away."

For more on how to make the right adjustments that will get you unstuck and out of nascent product-market fit, apply to join PMF Method.

Level 2:

Developing

By Level 2, you’ve ticked through some of the classic milestones, such as building something 20 or so customers need, or getting to your first $1M in ARR. And while you haven’t totally figured it all out, there’s also much more repeatability in your customers’ needs, the messaging that resonates, and the product solution you’re delivering.

Developing PMF is when you're starting to see glimmering signs that the marginal customer is more within reach — but it by no means feels easy yet. This is one of the reasons why Level 2 is one of the two levels that the majority of companies get stuck on. Think of it as reaching "lite" product-market fit.

What it Feels Like:

After Lattice’s product pivot, the difference in traction immediately felt clear to co-founder Jack Altman. “It was very obvious what market pull looked like then. We had people paying us annual upfront contracts without ever touching a real product, just on our design mocks — which couldn't be more different than the experience we’d been having with OKRs,” he says.

“There were leads coming organically from all over the place. People were telling their friends about us. People would say, ‘I'm kicking off this performance cycle in two weeks and I need this feature. You don't have it yet. Can we schedule time tomorrow to talk it through so we can help you build it?’ I think we booked twice as much revenue in the first month on that product than we had booked in the previous year on the last one.”

"Once you've got something that's going to work, it's going to work even in the face of a pretty undeveloped, incomplete, semi-broken product, which we certainly had at this stage."

What it Looks Like: A Case Study on Developing Demand, Satisfaction, Efficiency in Action

Let’s rewind the clock back to when Looker was at Level 2, roughly from March 2013 to Nov 2014. The startup emerged from stealth in March 2013 with a 34-person team and 20 customers, many of which were also in the First Round community. For co-founder Lloyd Tabb, this was the stage when he knew they were onto something. “By the time we had 20 customers, I knew it was going to be big,” he says.

By August 2013, they’d made enough progress to raise a $16M Series A round. By November 2013, they’d hit the coveted $1M in ARR milestone and grown to over 40 customers. New channels outside of warm intros were proving successful, from outbound and sales prospecting with two SDRs, to the potential of partner marketing with AWS Redshift and Snowplow. At this stage, that repeatability was starting to peek through. The Looker team had a better sense of who they were selling to (see their ICP from their Jan 2014 board deck below), having recently closed clients like Thumbtack, The RealReal, and Gilt. They were interested in going upmarket, and although they landed their first enterprise logos in April 2014 (eBay’s Venmo and NYTimes’ Baseline), for the most part, enterprise remained “elusive” at this level.

By July 2013, there was an average of 1600+ hours spent per month by customers in Looker. As the team put it in a board update, they continued to see amazing satisfaction by “maintaining insane referenceability and minimal churn (3).” As for efficiency, by the end of 2013, their CAC was $54,000 with a payback period of 19 months. At this time they noted that from first meeting to close ranged from two to seven months, with three months as the average. Customizations were still cropping up, as white-labeling and self-service had unique requirements. While sales process improvements were underway, their unique forward-deploy trials were still taking 30-40 hours, which needed to be brought down.

As for our example company at this level, meet Hire Hero, a fictional interviewing platform that uses AI to help teams hire better. They've got 18 full-time employees. They recently raised a $10M Series A round, and they've got a burn multiple of 4.2x. That's not where it should be — but at least they know what it is.

Let’s walk through each of the dimensions of product-market fit:

Demand: They’re at $1.2M in ARR and they have 22 customers. Their average sales cycle is 32 days, but that's an improvement over 47 days. One promising sign is that their most recent five customers are paying twice as much as what their early customers paid. Increasing ACV is a very strong sign on the demand side.

Satisfaction: This team has been around long enough to actually track renewals, and four of their customers have renewed. After selling for more than 12 months, four customers have churned, which isn’t ideal, but two of those were non-regretted. This is pretty typical. As the product direction changes, you’ll often realize that certain early customers are just not the right fit anymore. Additionally, weekly active usage is going up. The team is running classic NPS style surveys and getting roughly half nines and tens.

Efficiency: At this stage, it’s still not a focus, but at least they know they're at 65% gross margin. Software companies should be shooting for 75-80%+ when it comes to gross margin, so something to improve on. Their onboarding has gotten 15% faster. And very critically, fewer customizations are being asked for by each of their customers, meaning they’re able to sell the same product to now 22 customers.

Benchmarks:

These are the benchmarks that we would consider very typical of Level 2:

Team size: Up to 20 people.

You're either a Seed or Series A company.

Demand source: Early signs of a scalable channel that doesn't depend on warm intros from your VCs or your friends.

Without a warm intro, your first call to closed-won percentage is approaching 10%.

“Magic Number” (ARR/CAC) in the .5 to .75 range.

5-25 customers.

$500K to $5M ARR.

Some renewals, 10-20% regretted churn, NRR at least 100%.

Not less than 50% gross margin.

Not worse than 5X burn multiple.

What Matters Most:

To level up, your priority needs to shift to demand. Here’s why: We’ve seen true grind-it-out founders muscle their way to 20 customers through sheer willpower and effort. But you can’t will your way to 100 or 200 customers — the satisfaction and demand for the product are starting to do the work for you.

Startups need to find a way to effectively drive demand. But in addition to working on lengthening those lines out the door, you still have to maintain the satisfaction bar that you’ve reached. And while efficiency still isn't the primary concern, it’s something that you’ll need to pay more and more attention to. Now is the time to start thinking about if this is going to be an efficient business, and starting to do the work to make it one.

The most helpful levers for pushing on demand are typically fine-tuning your product positioning and finding scalable channels, whether that’s outbound sales or SEO, paid marketing, or referrals.

For Vanta’s Christina Cacioppo, the latter is an area she would revisit with a time machine. “There was this kind of tight call-and-response where someone in a First Round community Slack channel or a YC forum would say ‘SOC 2’ and someone else would say ‘Vanta,’” she says. “We were so proud of ourselves with our brilliant guerilla marketing or whatever we thought we were doing, but I think what actually happened is we really underinvested in learning how to explain what we were building, outside of ‘Vanta gets you SOC 2, and that's important for your business.’ In retrospect, we should have started on some of that earlier versus coasting on what was initially great word of mouth.”

"Word of mouth is wonderful, but in B2B you also need to scale ways you're acquiring customers. You need to start on that work earlier than you think. "

Yellow Flags to Watch Out for:

If you’re still unsure of whether your business can be classified as developing product-market fit, here are the yellow flags we recommend watching out for:

Current customers are happy, but you're having trouble opening the floodgates.

Regretted churn is greater than 20%. People bought your product and paid for it and just weren't happy — and one out of five of them is churning off.

Starting to get concerned about your burn multiple, e.g. you're burning $200K per month and only bringing in $20K net new ARR per month, which would put you at a less-than-stellar burn multiple of 10. (You’re aiming for as close to 1 as possible, or even below 1). But you feel like if you stop spending the money you're just going to stop growing.

Sales cycle is taking too long and you lose deals late in the funnel. You start to lose to competitors. And you're just not feeling the urgency from potential customers.

You're struggling to hit the price point that you want. This is often a signal that customers see your product as a nice-to-have versus a must-have. You often hear “we don't have the budget,” or “it's not the right time for us,” in conversations.

For more on how to get your sales machine firing on all cylinders to propel your company out of developing product-market fit, apply to join PMF Method.

Level 3:

Strong

In our experience, the majority of startups never get to this level. If you get to strong product-market fit, your company has the potential to be very valuable.

The big difference between Level 2 and Level 3 is that the demand floodgates have opened. There’s even more repeatability. Demand is coming inbound. People have heard of you. The company feels like it’s humming. You know who your customer is with much more specificity (for example, the head of security at a company with 250-1000 employees who’s already using a Palo Alto Networks product). Your costs to acquire them are still a little high, but you’ve found that (most of the time) you can engage them with a clear and consistent message that resonates. You’re able to deploy a solution with little customization that delivers a ton of value to the customer.

What it Feels Like:

This is the stage where most of those PMF analogies you’ve previously heard start to make sense — you start to really feel the effects of product-market fit.

David Hsu from Retool put it this way: “We talked to someone who said that finding product-market fit was so visceral that you immediately felt it — like a geyser exploding. And we honestly never felt that in the first couple years. At Retool every early customer we got, whether that was number four or number 14, felt like the last customer we were ever going to find. It felt more like rolling the stone uphill. If you stop pushing, it'll start rolling back on you immediately. That's how it felt until we had a few million in ARR — that's when the boulder went down the other side, and we had to chase it to keep up.”

Here’s how Jack Altman from Lattice describes it: “The biggest shift was in the ease of getting leads. I remember thinking, ‘I don't even know where these leads are coming from.’ And more just kept showing up every month,” he says.

For Verkada’s Filip Kaliszan, the feeling was similar. “After our first year of sales in 2018, those next two years were crazy. We were barely keeping up with production. We had to scale all the systems. A lot of things had to happen in the span of the next 12-18 months in order to deliver on everything that customers were hoping the solution was going to do for them. That in itself was a very formative and tricky part of the journey.”

For Plaid’s Zach Perret, this level felt noticeably different. “2016 to 2017 is when we knew we had very strong product-market fit, and that was mostly because we just saw rapid growth of many of our customers,” he says.

“This is around when Robinhood and Coinbase started to take off, and we saw it in our numbers. One of the benefits of being a platform company is that you're able to install really early with a customer and then grow over time, and that scale is really, really lovely,” says Perret. “For example, we eventually branded a portion of the user signup flow within Venmo and other apps. And that minor branding actually drove a lot of demand for our product because people would see it and they would say, ‘Hey, this is a new financial services experience. I should call Plaid because Plaid helped build this one.’ And so we had this nice cycle of our customers doing well, driving demand back to us and then so on and so forth every time,” he says.

“But keep in mind, by this point it had been four or four and a half years since we started the company. And so a lot of the early journey was based on faith and belief that this market would exist, on good early signals that were partially real and partially manufactured by the work that we'd done.”

What it Looks Like: A Case Study on Strong Demand, Satisfaction, Efficiency in Action

Let’s start again by tracing back to when Looker fit into Level 3, roughly from November 2014 to December 2015. By November 2014, the team had passed the $5M ARR mark. CEO Frank Bien put it best in an email update to us: “The general feeling is that lots of companies can make it to $1 or 2M ARR, but hitting 5M shows you’ve built something very real and sustainable. Also impressive is how quickly we hit this point.”

In February 2015, the company raised a $30M Series B round, noting they’d grown to 110 employees, and increased revenue by 400%. At this point, Looker had 250 customers, adding new customers such as Uber, Instacart, Plaid, and Etsy. Continuing to open up new channels, the team closed its first reseller deal in Q2 2015 and started expanding into Europe, opening their first EMEA office in London. The team was focused on growing organic inbound through PR, community, content & thought leadership, in addition to scaling their partnerships. For example, early in 2015 bringing on Segment and Snowflake was a big win, as was being selected as one of three top launch partners for Microsoft SQL DW & Azure. However, a main focus during this period was fine-tuning their positioning, to better appeal both to data experts and general business users.

Customers experienced as much as 80-90% user adoption across an employee base. By the end of 2015, 97% of customers were accessing Looker at least once per day, CAC had decreased to $45,300 and payback period was down to 17.5 months. Gross margin improved from 62.5% in 2014 to 72.6% in 2015. The sales trial model continued to get more efficient, and the company had a 70% trial to win rate. But perhaps what was most impressive as efficiency shifted into the forefront was their planning accuracy: In seven years, the Looker team never missed a bookings plan, achieving a rare 28-quarter streak of pure execution.

For our Level 3 case study, let’s introduce GuardDog, a fictional incident management tool to help security teams seamlessly identify and address security issues. They have 64 full-time employees and are planning to raise a $25M Series B. Their burn multiple is now 2.1, which is getting respectable.

Let’s walk through each of the dimensions of product-market fit:

Demand: GuardDog has 88 customers. With $10M in ARR and 14% sales conversion, they've got inbound and outbound channels that are working, and awareness is starting to spread. They're starting to see word of mouth traction, which is very common at this level. (Think: “Oh, you're a startup? You need a security solution, you should choose Guard Dog, that's what all the startups are using.”) They're projecting 3x growth in ARR over the next 12 months.

Satisfaction: They're at 108% net revenue retention, and 8% regretted churn per year. Quarterly user engagement has gone from 5.5 average users per customer up to nine.

Efficiency: GuardDog is getting into the respectable zone here. The team did a ton of work both on the infrastructure side, and the services side to improve to a 71% gross margin. Onboarding has gotten faster by 60%.

Benchmarks:

Team size: 30-100 people.

Stage: Series A/B/C company.

Demand source: 1+ scalable channels (you’ve cracked marketing and sales). >10% of your inbound is coming from referrals/WoM.

1st call to closed won 10-15%.

Magic number >.75, CAC payback <18 months.

25-100 customers.

$5-25M ARR.

>110% NRR.

<10% regretted churn.

60-70%+ gross margin.

Burn multiple in 1-3X range.

What Matters Most:

To reach the next level, now is the time that you have to get serious about efficient economics. CAC payback, LTV to CAC ratio — these are all the metrics that really start to matter. (Specifically you want to see a CAC payback period under 18 months, and LTV/CAC greater than three.)

If you eventually want to be valued well in the public markets (which you’re probably starting to think about at Level 3), you have to become more efficient — while still sustaining satisfaction and demand. Focusing on refining your GTM motion (inside sales, outside sales, layering on channel partnerships) and figuring out broad awareness building is key here.

The difference between strong and extreme product-market fit is that you have to successfully stay on that growth curve and make the whole operation more efficient at the same time. It’s a highwire act.

Yellow Flags to Watch Out for:

What we’ve observed most at Level 3 is that this is when real competitors start to emerge — before you may have been flying a bit under the radar. But now your product is clearly working and other startups or mid- to late-stage companies have started to notice that.

Many startups also get caught in the “spend money to grow” trap, caught between investor pressures to lower your burn multiple, but also your own fears that you’ll stop growing if you go below 2-3X.

Here are the yellow flags we recommend watching out for:

You’ve got a little bit of a leaky bucket: NRR below 90%, regretted churn greater than 10%.

Referrals and word of mouth have started to plateau.

Growth is slowing down. You grew 3X each of the prior two years, but you're struggling to hit 2X this year.

You found your first scalable channel, but it's gotten saturated, and you're struggling to find a new channel.

At Looker, Frank Bien’s mandate was to figure out how to scale Lloyd Tabb's early sales approach into a model-driven company. Here’s how he thought about balancing these competing interests: “After crunching the numbers, we saw that by the time we had 2,000 customers, we could be doing $100 million dollars in ARR, and on the path to going public. That was the model from 2013 on. And as a side note, we were pretty spot on — we were at 1,700 customers, so we actually did a little better than we predicted,” says Bien.

“Lloyd’s early sales intuition was right, you had to do a robust proof of concept. It reminded me of Palantir’s forward-deployed engineers. We wanted to do an inside sales motion of that. Those salespeople had to be supported by an embedded technical person. But you have to know your model backwards and forwards to make a bet like that,” says Bien. “We knew the margins on the costs we were sinking into pre-sales support made sense. But if we had been unsure whether it was going to take 2,000 customers or 100,000 customers to reach the $100 million run rate, that would have been an incredibly risky move — we very easily could have been lighting our VC dollars on fire.”

“People often create models to drive valuation, they’re always trying to do 2x the plan. In my opinion, that’s the most dangerous, company-killing move you can make. We’ve never adjusted our plan based on any external investor influence or a valuation we were trying to achieve in an upcoming round. We did, of course, put our foot down on the pedal from time to time, but it was only when we saw opportunity in the business,” says Bien. “For example, when we first started trying to expand into enterprise, we were testing the waters. Once it started working, we invested more in our enterprise go-to-market efforts and bumped up our targets.”

Bien notes that when it comes to setting your plan, you want to maximize growth, but you also want it to still feel like a win. “It’s tempting to throw the plan numbers up much higher, and think that if you put the rabbit a little bit farther in front of the dog, it’ll run much faster. But that’s not how it works. It mostly just leaves you feeling like you’re treading water, which over the long run, actually slows you down,” he says. “We set our numbers according to our model, and we were ambitious, but not crazy — and in the end we got there faster.”

"When it comes to setting your targets for the quarter, don’t stray too far from your model. Go faster where you can go faster, but don’t take a blunt force approach that makes your team feel like they’re drowning."

For more on how to build a more efficient GTM motion that pushes you past strong product-market fit, apply to join PMF Method.

Level 4:

Extreme

Finally, Level 4: extreme product-market fit, which should be the goal of every startup.

If you’re at this stage, repeatability shines through in your ability to win over customers that are in your crisply defined target persona — it doesn’t mean you have a 100% conversion rate, but there’s tremendous consistency.

This is also often where a company’s brand often begins to inflect. With more widespread recognition, you may be on the cusp of becoming the “Kleenex” of your category — making it dramatically easier to capture the marginal customer. (In the startup context, think of Vanta being synonymous with SOC 2, for example.)

But a founder’s quest for growth never really ends, so the journey here isn’t over — the challenge becomes finding product-market fit over and over again as you go multi-product. You feel your organization is ready for the new challenge of expanding your TAM and launching a new bet outside your core product.

What it Feels Like:

When building wholesale marketplace Faire (last valued at $12.6B), Max Rhodes remembers struggling with the question of when to expand. “We'd heard horror stories from other companies that tried too early. But we got good advice that you shouldn’t expand until you feel like you're pedaling at half speed, until you as the CEO are comfortable with all the progress that is being made in your core market,” says Rhodes.

“We made a pretty explicit choice to really focus on nailing things in our core market. It wasn’t until late 2019, so three years in, that we decided we were ready to go international and to go after apparel — we made the decision to do both simultaneously,” he says.

“There were a few boxes that I felt like we'd checked. One, we had the growth model figured out. I felt comfortable that growth was predictable and that we were just going to keep growing in the U.S., and that we built a big enough lead on domestic competition that we didn't need to figure out new things to accelerate our growth. We were more in optimization mode than really needing deep innovation,” says Rhodes.

“Second, we also had a leadership team in place for all the key functions. That felt stable. And I no longer felt like I was having to put out fires all day every day because this person was going to quit, or this problem popped up that we didn't know the answer to. My involvement in the day-to-day operations of all the functions no longer felt necessary. It felt like things were mostly working,” he says.

“And then the third thing is we had our unit economics figured out. I was no longer worried that we would run out of money if we kept growing. We had good payback periods. We were historically a very low margin business. We were negative contribution margin for the first two and a half years, but we'd finally cracked the code on getting to positive contribution. And so it felt like the systemic risks to the business, whether it was competition, hurting our growth, capital risk, or people execution issues, were in a solid place.”

"Earlier in company building, you’re going uphill on a bike and pedaling as hard as you can. When it comes time to expand your TAM, you're looking for that feeling where you’re not going downhill, but you’re on a flat road and there isn't as much resistance. You can pedal a bit and let momentum carry you forward."

What it Looks Like: A Case Study on Extreme Demand, Satisfaction, Efficiency in Action

Our example company for this level is called Metriq, a fictional intelligence platform that delivers self-service analytics and reports so teams can make decisions faster. They're at 186 employees and they just raised a $75 million Series C. Their burn multiple is looking very good at .87 — last month they brought in $2M of net-new ARR, and only burned $1.73M.

Let’s walk through each of the dimensions of product-market fit:

Demand: They've got 262 customers. They're almost at $30M in ARR. Sales conversion is 24%. Their ACV is $112K. They grew ARR 3x over the prior 12 months, and are going to hit 2x over the next 12 months. What’s more is that they can actually project the next 12 months of revenue growth with a fairly high degree of confidence.

Satisfaction: Their customers are using the platform regularly and without prompting — the product is that important to them. They're at 123% NRR, and their regretted churn is only 6%. 13% of their inbound leads are just coming from customer referrals. The team gets two to three positive customer emails per week, completely unsolicited.

Efficiency: The sales, onboarding, and customer success teams are running smoothly. They've got repeatable playbooks. Gross margin is up to 86% and they’re at an 11 month CAC payback.

Benchmarks:

Here are the benchmarks for a company that has extreme product-market fit:

Team size: 100+ people.

Company is at Series C or beyond.

Demand Source: 2+ scalable demand channels.

1st call to closed won >15%.

Magic number >1, CAC payback <12 months.

100+ customers.

$25M+ ARR.

>120% NRR.

<10% churn.

80+% gross margin.

Burn multiple 0-1X.

What Matters Most:

Whether it’s Salesforce, Stripe, or Datadog, all the legendary enterprise companies have managed to enter multiple markets with multiple products and reach extreme PMF time and time again in new customer segments.

If you want your company to compound value, you’re not done with growth in year six or seven, or just because you’ve reached a certain size. Growing over a long period of time is actually the act of finding extreme PMF over and over again. The very best companies are forever focused on expanding TAM and re-finding PMF in new markets.

In our experience, most founders struggle with the timing, and start thinking about expanding TAM too late. When you’re focused on getting the core business to fire on all cylinders, it’s hard to split your time. Atlassian stands out as an example to take inspiration from here — the company pursued this work much earlier than most.

“We created our second product, Confluence, in Atlassian’s second year, which is really unusual — especially when you’ve got a breakout product like Jira that’s growing really nicely. Conventional company-building wisdom would say not to do it — there’s still a ton of work you need to do on the first product, and it will fragment your focus once you start working on a second thing, which could be a death sentence for a young company,” says Jay Simons.

But not only did Confluence become a cornerstone of Atlassian’s product suite, Simons also spots plenty of less-tangible upsides. “We began to build this muscle around cross-merchandising, cross-selling, and upselling. How do you think about pricing and packaging around multiple things? How do you do product planning and prioritization and budgeting and staffing? At a really early age at Atlassian, we began to wire our brain to think about all of those things that companies need to do as they get bigger,” he says.

“It’s harder as you get bigger too, because the product you add actually needs to be bigger. For a company like Atlassian that has individual products that are hundreds of millions of ARR, a new thing that you add has got to grow pretty quickly, and it’s got to have a big market it can grow into,” he says.

Timing aside, the other hurdle is tackling the question of which path to take once you hit that inflection point of needing to grow your TAM. We like this framework from Persona founder Rick Song:

Once you’ve reached extreme product-market fit and are ready to attempt to do it all over again, you can effectively expand your TAM — which is how you compound revenue — by remixing one (and eventually all) of three components: your product, your market or your buyer.

That could look like:

Creating new product use cases by adding new features and functionality.

Creating a net-new product that you sell in the same market to the same buyer.

Taking the same product and expanding into a different market (whether that’s a different sector or moving upmarket/downmarket).

Selling the same product in the same market to a different buyer.

Over time, you will likely need to expand all of these. Let’s return to Atlassian. For simplicity’s sake, say Act I was JIRA (a single product) sold to an engineering leader (buyer) at companies between 10 to 100 people in size (market segment). You can change any of those three elements — but in most cases, it’s best to do this serially.

In our Atlassian example, say Act II was taking the same product and selling it to security leaders to manage all the security tickets (new buyer, same market segment). Say Act III was introducing Confluence (a new internal wiki product), in many cases sold to the same buyers and market segment.

Or consider how Salesforce sells into healthcare, financial services, and government. The product use case is relatively similar, the buyer may be different or the same, but the market segment is very different. Other times, the buyer remains relatively consistent but the product use cases change. In its most simplistic form, Amazon’s AWS has hundreds of use cases and SKUs sold into the same (or a similar) buyer.

As you can see, there are countless combinations to explore. But in our experience, when most founders think about building concentric circles around their core business, too often they concentrate on selling a new product use case into an existing buyer. It seems like a lower lift, in the sense that you already have the customer. And sometimes that's the correct thing to do — Square expanding into lending is a great example — but if that’s the only path you pursue, there will be a ceiling on your TAM.

What’s crucial is that for each one of these new bets, you need to get to strong and extreme product-market fit. In some cases, the journey is much shorter, given the work your company has already put into understanding a customer or developing a market. But in other cases, this requires starting at the very bottom of the ladder, moving through the levels of product-market fit all over again. In other words, a company might have extreme product-market fit with one product, buyer and segment, and perhaps only nascent product-market fit for another product with the same buyer and segment. That is the journey of building compounding revenue over years and then decades.

It’s like you’re assembling a layer cake over many many years. You’re adding on new features, new products, new customers, new market segments — trying to stack your way to a multi-billion dollar valuation without knocking the whole thing over. That’s been the recipe for every fantastic B2B company.

That journey of climbing your way to extreme product-market fit only to have to move through the levels once more is certainly daunting — particularly when you remember how tough those early days without traction were. “As much as I now joke about Vanta’s early days and how confused we were with all of our different startup ideas, the truth is that period is really rough,” says Christina Cacioppo.

“From the outside, you can romanticize a founder’s life and think, ‘The world's your oyster. You can build whatever you want. You're going to start a company, it'll be great. You get to decide everything.’ And that's all true, but in the day-to-day, it's more like, ‘What am I doing? Does anyone care? Will anyone ever care?’ There’s so much in the early days where you can't tell if you’re doing it wrong. Having a group of other people going through a similar experience to talk about that with and normalize some of the uncertainty is really, really helpful. It can help you figure out if it’s an idea that you’re pulled toward because you’re just looking for something in all of the uncertainty, or if it’s actually viable.”

We’ve purpose-built PMF Method to solve those challenges. Building a company is lonely, but we’re firm believers that there’s no cure like working alongside a tight group of other top 1% B2B founders at your same stage. Apply here to join them.

This article was about what extreme PMF looks like, but in our program, we dive into the details of how you can get there — you can preview the other seven sessions you’d learn from in the program here.